The final plague outbreak in Scotland 1644–1649: Historical, archaeological, and genetic evidence

The final plague outbreak in Scotland 1644–1649: Historical, archaeological, and genetic evidence

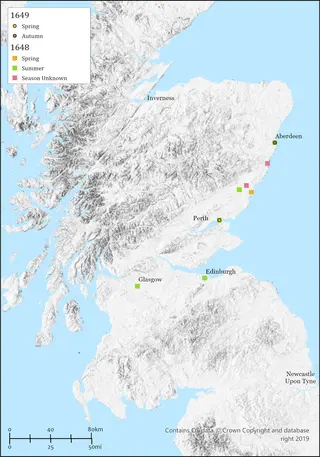

This paper has several aims: to determine if Yersinia pestis was the causative agent in the last Scottish plague outbreak in the mid-17th century; map the geographic spread of the epidemic and isolate potential contributing factors to its spread and severity; and examine funerary behaviours in the c...

This paper has several aims: to determine if Yersinia pestis was the causative agent in the last Scottish plague outbreak in the mid-17th century; map the geographic spread of the epidemic and isolate potential contributing factors to its spread and severity; and examine funerary behaviours in the context of a serious plague epidemic in early modern Scotland. Results confirm the presence of Y. pestis in individuals associated with a mid-17th century plague pit in Aberdeen. This is the first time this pathogen has been identified in an archaeological sample from Scotland.

Fear seems to have been so great in some areas that those dying of the plague might not be buried at all. An anecdote from Tillicoultry concerning a man that had died suddenly, the assumption being from the plague, recounts that “the people were afraid to touch the corpse or even enter the house. It was pulled down, and the small eminence, which this occasioned, was called Botchy Cairn” . Similarly, McKerral relays a story concerning the outbreak in Kintyre where green knolls on Kilkivan farm attest to the presence of houses that were left to decay and collapse on top of their occupants: plague victims.

While fear of burying plague victims may have led to their abandonment, there also apparently a fear of improper burial to the extent that a further apocryphal anecdote for Highlanders to “order their coffins while still alive” to ensure proper burial.

Finally, another story has it that a plague victim managed to convince friends to dig his grave, within which he lay until he died.

It is unclear if a general fear of the dead and contracting the Pest from plague victims can be used to characterise mid-17th century Scottish public opinion. Arguably, plague pits and mass burials in general were more a practical response to the logistical difficulties associated with disposing of the dead on a large scale.

Having the plague was not a one-way ticket to a plague pit and, indeed, there are many examples of plague victims receiving normative and caring burial treatment despite any potential risks to the bereaved.