- www.technologynetworks.com Are Chimps Building Cultures Like Humans? New Research Says Yes

Chimpanzees display an early form of cumulative culture, with successive generations refining tool-use practices for complex tasks like termite fishing. A study highlights how female migration facilitates the transmission of these behaviors.

- www.businessinsider.com Russia's invasion is showing the West war isn't just about having the best weapons — it's also about having more

The West focused for decades on advanced and complex systems over a sheer volume of weaponry. Russia's invasion of Ukraine shows that needs a rethink.

- dynomight.net OK, I can partly explain the LLM chess weirdness now

(“make LLMs play better with one weird trick”)

- www.techradar.com Prediction: 2025 is the year quantum computing advances from physical qubits to logical qubits

This transformative technology is poised to take a giant leap forward

- www.bloodinthemachine.com Bluesky's success is a rejection of big tech's operating system

No bad adtech, no AI, no throttling links. Bluesky is a booming because it's everything big tech is not

Greetings all —

Hope everyone’s as well as can be out there, after The Election. Personally, I spent much of last week sleep-deprived and fried, having come off a week-long flu (during which I streamed a deluge of horror movies) right into the election week chaos. And then I immediately got another nasty cold—the joys have having small kids in school—so I remain uncertain as to what is actually real, and what is a feverish, semi-hallucinated daydream, and I’m just going to revel in that for a while.

I’m working on a longer post about what the coming Trump years might hold for the tech world—the vast majority of it concerning, from an anticipated rise in surveillance tools required to enact mass deportation, the further entrenchment of tech monopolies, Elon Musk’s incipient reign as the nation’s most powerful government tech contractor, and a frenzied boom in crypto and defense tech that has already begun—but in the meantime, I want to touch on a story that’s cause for a bit of hope, in spite of everything.

This newsletter is made possible by subscribers—it’s free to read, but I’m only able to do it thanks to paying supporters. If you find this stuff useful, please consider chipping in:

I’m talking, like so many other tech pundits, about the ascent of Bluesky. The decentralized social network hit 15 million users last week, and claimed the no. 1 spot on the App Store, above ChatGPT and TikTok. At time of writing, it still held that spot, all thanks to users fleeing Musk’s X-né-Twitter, the introduction of some good and innovative features, and the refreshing sense that someone is actually successfully building a place on the internet with users, not consumers, in mind. In 2024, that is enough to qualify it as a nearly utopian project.

So many people were signing up for Bluesky every day last week that its servers were overloaded for intermittent stretches.

Bluesky has spent the last two years or so hovering on the verge of a breakthrough, primarily because it’s the go-to home for Twitter and X refugees. Musk bought Twitter in 2022; when he started re-platforming users previously banned for hate speech and harassment, boosting his own feed, introducing pay-to-play features, and so on, many fled the platform. Bluesky, which was co-founded by Jack Dorsey, had its first big moment in spring 2023, when a group of power users set up shop. I wrote about that moment for the Times; Bluesky felt freewheeling, weird, and open to low-stakes posting in a way social media hadn’t in years.

Since then, it’s grown in spurts and starts, attracted dedicated users, and enjoyed boom periods whenever Musk does something divisive, like taking X offline in Brazil rather than meet with regulators, or removing its blocking feature. But what’s happening now is on a different level. X was already a toxic cesspool, brimming with misogyny, spam porn accounts, and door-to-door AI salesmen. But the fact that Musk helped elect Trump became too much for many users to bear—users are defecting, closing their accounts, and heading to Threads, Mastodon, or Bluesky.

It’s become a badge of honor on Bluesky to post your X account deactivation screenshots, and I’ve lost hundreds, many thousands, of followers since the exodus began. And I’m happy for them! X is a mostly miserable place. But it’s also, as Malcolm Harris once remarked to me over coffee, where the fight is. And that’s never been more true; if you are a semi-unhinged person (like me) who uses the platform to comment, criticize or otherwise yell about the parade of injustices handed down by tech companies and billionaires, it’s still probably the best place to do that; its where your commentary on such matters is most likely to be seen where it might matter. (Whether or not posting has any such utility at all is a question for another day; I have been the butt of much scoffing and many an argument because I actually think it does, to a point.)

But for all other modes of posting—jokes, historical anecdotes, community-building, general news-sharing—Bluesky is better. Much better. And that’s where I hope to be spending most of my time going forward. And there are a few things fueling the boom this go round, besides the fact that it’s a Twitter clone that is not owned by Elon Musk.

Mostly, the starter packs. Bluesky lets users curate easily accessible and shareable lists of recommended users for those just joining the platform. This is a kind of ‘why don’t we put wheels on luggage’ sort of innovation that, in hindsight, it’s wild that no other social network had thought to do before. It serves two purposes: It gives new users a quick onramp onto the platform, and it gives users included in the packs new audiences; everyone wins. The biggest challenge any social media site faces is successfully activating the network effect—sites like Bluesky are only as good as the user bases they can attract, and sustain.

And thus the question of the week was: Does Bluesky have the juice? Max Read asked precisely that in his newsletter, concluding, essentially, that it has some juice but perhaps not quite enough to become whatever Twitter once was:

Bluesky acts more like a particularly large Discord server--a place to socialize, bullshit, banter, and kill time--than it does like a proper Twitter replacement. For many people I think this is fine; I’m not sure how much the world needs a “Twitter replacement” anyway. But the distinction is still important. Part of what’s made Twitter so attractive to journalists is that it’s relatively easy to convince yourself that it’s a map of the world. Bluesky, smaller and more homogenous, is harder to mistake as a scrolling representation of the national or global psyche--which makes it much healthier for media junkies, but also much less attractive.

Aja Romero and Adam Clark Estes are more sanguine at Vox, noting that it delivers the fun, weird vibes of old Twitter, and “could usher in a brighter future for social media.” Ryan Broderick goes further: “I’m comfortable saying that Bluesky won the title of The Next Twitter... Though, there is a bigger question that hangs over Bluesky. Which is, exactly how big can a text-based, non-algorithmic feed actually get?”

Those constraints are, in part, exactly what makes Bluesky appealing, Jason Koebler notes at 404 Media, in a piece called “the Great Migration to Bluesky Gives Me Hope for the Future of the Internet”:

the energy on Bluesky is exciting, that the app and website are very usable, and that, as a journalist, I appreciate a platform that does not and says it will not punish links in any algorithm and which mostly operates in reverse chronological order… What’s happening on Bluesky right now feels organic and it feels real in a way no other Twitter replacement has felt so far, and it feels better than X.com has been ever since Elon Musk took over.

I have used Bluesky a little bit here and there since logging on a year and a half ago, and while it’s always felt better, it’s also been lacking that element that Read highlights; the feeling of universality; that you really are interacting with a broad spectrum of voices. Now it’s getting closer, even if it still maintains an oversampling of a certain type of user—left-liberal, online hyper-literate, etc.

But even more than its relative success, what’s worth underlining, to me, is that it is succeeding amidst a tech ecosystem that is all-in on data extraction, algorithmically optimized ad tech, and the mass distribution of AI content. This is why so many journalists and techies and posters are cheering so loudly for the platform. (Also because the starter packs helped many of them acquire thousands of followers overnight, thus motivating them to write about them; another reason they are genius.)

Bluesky is building something for real people; it’s actually listening to what those users want, and tailoring their product and experience accordingly. Wild. And so you get things like a generally real-time, reverse chronological feed, a very customizable user experience, with a wide array of options for deciding how you want your content to be seen and who you want to be able to follow you, and you get responsive content moderation, even though this is surely abetted by the lower volume of posts.

You get promises that Bluesky will not throttle links, like X does, so creators and writers can share their work without fear of an algorithm penalizing them for doing so. That this is a selling point, three decades into the commercial internet—we will not punish you for sharing hyperlinks—is bleak in its own right, but that’s where we are. Bluesky also has a laudable enough stance on AI, stating that it does not train any AI models on posts, and does not intend to.

All this stuff—user customization, creator-friendly policies, and simple-but-smart ideas like the starter packs—amounts to a blast of fresh air to the face of an online world that is dominated utterly by extractive tech monopolies who long ago waved goodbye to any nominal notion about caring about the user. Mark Zuckerberg just said bring on the AI slop. X is an intensely hostile user experience—share a link to your writing, your artwork, a news article, anything, and its algorithm shows the post to fewer people. That’s to say nothing of the nonexistent content moderation and rampant racism. Google is flooding its search result pages with unreliable AI summaries, further diminishing the standing of news and human-written articles.

The online world has become so hostile to users that Bluesky’s pitch of ‘here is a straightforward feed of text-based user-generated posts that we promise not to mess with’ is revelatory. Its scaling model and raison d’être are a very rejection of the platforms that have colonized the rest of our digital lives, and relentlessly commodified them. No wonder everyone seems to be rooting for its success, even if there are, pointedly, no guarantees those ideals will remain in place.

Because look, Bluesky is far from perfect. It recently raised a $15 million series A funding round led by the ominously-named Blockchain Capital, though leadership promised it would “never hyperfinancialize the user experience” with NFTs or crypto, and stressed it would remain focused on the user. And I wish it would go as far as Mastodon in its federation, allowing users full interoperability, as Cory Doctorow has called for. (Mastodon is, we should note, by any count, the more properly utopian project; more user control, no weird VC cash, etc—for me, at least, it just sadly doesn’t have the same juice. Most of my network simply isn’t there!)

I wish, as I posted on Bluesky, that it would do even more than that, and take this bright opportunity to expand on what it’s already started—and work to ensure that the user experience that has generated so much excitement won’t erode when Blockchain Capital wants to see some returns on its investment. Why not get wild here, and show how truly committed to the user you are: Maybe introduce a mechanism for users to have a direct say in platform governance matters? A Bluesky User Board? Or instead of looking to monetize via paid features or ads, test voluntary subscription offerings, as Signal and Wikipedia do? Lots of users have already signaled they’d pay a monthly fee to keep Bluesky pristine. Look, a luddite can dream here.

I’m in agreement with Rob Horning and Nathan Jurgenson—the better question than ‘is Bluesky the next Twitter’ is ‘what else might Bluesky become’? What possibilities are latent here? There is excitement over a text-based social media network, in 2024, the age of TikTok and streaming; how might that be channeled?

Bluesky is giving hope to people who spend long hours online precisely because it is purporting to be, and so far succeeding, at least in its very short lifespan, in being everything that big tech is not. No AI spam, no glitchy ad tech, no link throttling, no malignant billionaire owner. Bluesky is not just tapping into this wellspring of goodwill because it promises a return to the halcyon days of Twitter—but a return to the days before ossified, rent-seeking tech monopolies drove our collective online experience to hell.

- slate.com Why I ditched Buddhism.

For a 2,500-year-old religion, Buddhism seems remarkably compatible with our scientifically oriented culture, which may explain its surging popularity...

For a 2,500-year-old religion, Buddhism seems remarkably compatible with our scientifically oriented culture, which may explain its surging popularity here in America. Over the last 15 years, the number of Buddhist centers in the United States has more than doubled, to well over 1,000. As many as 4 million Americans now practice Buddhism, surpassing the total of Episcopalians. Of these Buddhists, half have post-graduate degrees, according to one survey. Recently, convergences between science and Buddhism have been explored in a slew of books—including Zen and the Brain and The Psychology of Awakening—and scholarly meetings. Next fall Harvard will host a colloquium titled “Investigating the Mind,” where leading cognitive scientists will swap theories with the Dalai Lama. Just the other week the New York Times hailed the “rapprochement between modern science and ancient [Buddhist] wisdom.”

Four years ago, I joined a Buddhist meditation class and began talking to (and reading books by) intellectuals sympathetic to Buddhism. Eventually, and regretfully, I concluded that Buddhism is not much more rational than the Catholicism I lapsed from in my youth; Buddhism’s moral and metaphysical worldview cannot easily be reconciled with science—or, more generally, with modern humanistic values.

For many, a chief selling point of Buddhism is its supposed de-emphasis of supernatural notions such as immortal souls and God. Buddhism “rejects the theological impulse,” the philosopher Owen Flanagan declares approvingly in The Problem of the Soul. Actually, Buddhism is functionally theistic, even if it avoids the “G” word. Like its parent religion Hinduism, Buddhism espouses reincarnation, which holds that after death our souls are re-instantiated in new bodies, and karma, the law of moral cause and effect. Together, these tenets imply the existence of some cosmic judge who, like Santa Claus, tallies up our naughtiness and niceness before rewarding us with rebirth as a cockroach or as a saintly lama.

Western Buddhists usually downplay these supernatural elements, insisting that Buddhism isn’t so much a religion as a practical method for achieving happiness. They depict Buddha as a pragmatist who eschewed metaphysical speculation and focused on reducing human suffering. As the Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman put it, Buddhism is an “inner science,” an empirical discipline for fulfilling our minds’ potential. The ultimate goal is the state of preternatural bliss, wisdom, and moral grace sometimes called enlightenment—Buddhism’s version of heaven, except that you don’t have to die to get there.

The major vehicle for achieving enlightenment is meditation, touted by both Buddhists and alternative-medicine gurus as a potent way to calm and comprehend our minds. The trouble is, decades of research have shown meditation’s effects to be highly unreliable, as James Austin, a neurologist and Zen Buddhist, points out in Zen and Brain. Yes, it can reduce stress, but, as it turns out, no more so than simply sitting still does. Meditation can even exacerbate depression, anxiety, and other negative emotions in certain people.

The insights imputed to meditation are questionable, too. Meditation, the brain researcher Francisco Varela told me before he died in 2001, confirms the Buddhist doctrine of anatta, which holds that the self is an illusion. Varela contended that anatta has also been corroborated by cognitive science, which has discovered that our perception of our minds as discrete, unified entities is an illusion foisted upon us by our clever brains. In fact, all that cognitive science has revealed is that the mind is an emergent phenomenon, which is difficult to explain or predict in terms of its parts; few scientists would equate the property of emergence with nonexistence, as anatta does.

Much more dubious is Buddhism’s claim that perceiving yourself as in some sense unreal will make you happier and more compassionate. Ideally, as the British psychologist and Zen practitioner Susan Blackmore writes in The Meme Machine, when you embrace your essential selflessness, “guilt, shame, embarrassment, self-doubt, and fear of failure ebb away and you become, contrary to expectation, a better neighbor.” But most people are distressed by sensations of unreality, which are quite common and can be induced by drugs, fatigue, trauma, and mental illness as well as by meditation.

Even if you achieve a blissful acceptance of the illusory nature of your self, this perspective may not transform you into a saintly bodhisattva, brimming with love and compassion for all other creatures. Far from it—and this is where the distance between certain humanistic values and Buddhism becomes most apparent. To someone who sees himself and others as unreal, human suffering and death may appear laughably trivial. This may explain why some Buddhist masters have behaved more like nihilists than saints. Chogyam Trungpa, who helped introduce Tibetan Buddhism to the United States in the 1970s, was a promiscuous drunk and bully, and he died of alcohol-related illness in 1987. Zen lore celebrates the sadistic or masochistic behavior of sages such as Bodhidharma, who is said to have sat in meditation for so long that his legs became gangrenous.

What’s worse, Buddhism holds that enlightenment makes you morally infallible—like the pope, but more so. Even the otherwise sensible James Austin perpetuates this insidious notion. ” ‘Wrong’ actions won’t arise,” he writes, “when a brain continues truly to express the self-nature intrinsic to its [transcendent] experiences.” Buddhists infected with this belief can easily excuse their teachers’ abusive acts as hallmarks of a “crazy wisdom” that the unenlightened cannot fathom.

But what troubles me most about Buddhism is its implication that detachment from ordinary life is the surest route to salvation. Buddha’s first step toward enlightenment was his abandonment of his wife and child, and Buddhism (like Catholicism) still exalts male monasticism as the epitome of spirituality. It seems legitimate to ask whether a path that turns away from aspects of life as essential as sexuality and parenthood is truly spiritual. From this perspective, the very concept of enlightenment begins to look anti-spiritual: It suggests that life is a problem that can be solved, a cul-de-sac that can be, and should be, escaped.

Some Western Buddhists have argued that principles such as reincarnation, anatta, and enlightenment are not essential to Buddhism. In Buddhism Without Beliefs and The Faith To Doubt, the British teacher Stephen Batchelor eloquently describes his practice as a method for confronting—rather than transcending—the often painful mystery of life. But Batchelor seems to have arrived at what he calls an “agnostic” perspective in spite of his Buddhist training—not because of it. When I asked him why he didn’t just call himself an agnostic, Batchelor shrugged and said he sometimes wondered himself.

All religions, including Buddhism, stem from our narcissistic wish to believe that the universe was created for our benefit, as a stage for our spiritual quests. In contrast, science tells us that we are incidental, accidental. Far from being the raison d’être of the universe, we appeared through sheer happenstance, and we could vanish in the same way. This is not a comforting viewpoint, but science, unlike religion, seeks truth regardless of how it makes us feel. Buddhism raises radical questions about our inner and outer reality, but it is finally not radical enough to accommodate science’s disturbing perspective. The remaining question is whether any form of spirituality can.

- news.sky.com The X exodus - could Bluesky spike spark end of Elon Musk's social media platform?

Even Google appears to trust X less, with one expert telling Sky News the search engine treats X competitor Bluesky as 10 times more important than Elon Musk's platform.

- mashable.com PSA: Your Twitter/X account is about to change forever

If you don't want Elon Musk to feed your tweets to his AI, now might be the time to leave the app formerly known as Twitter.

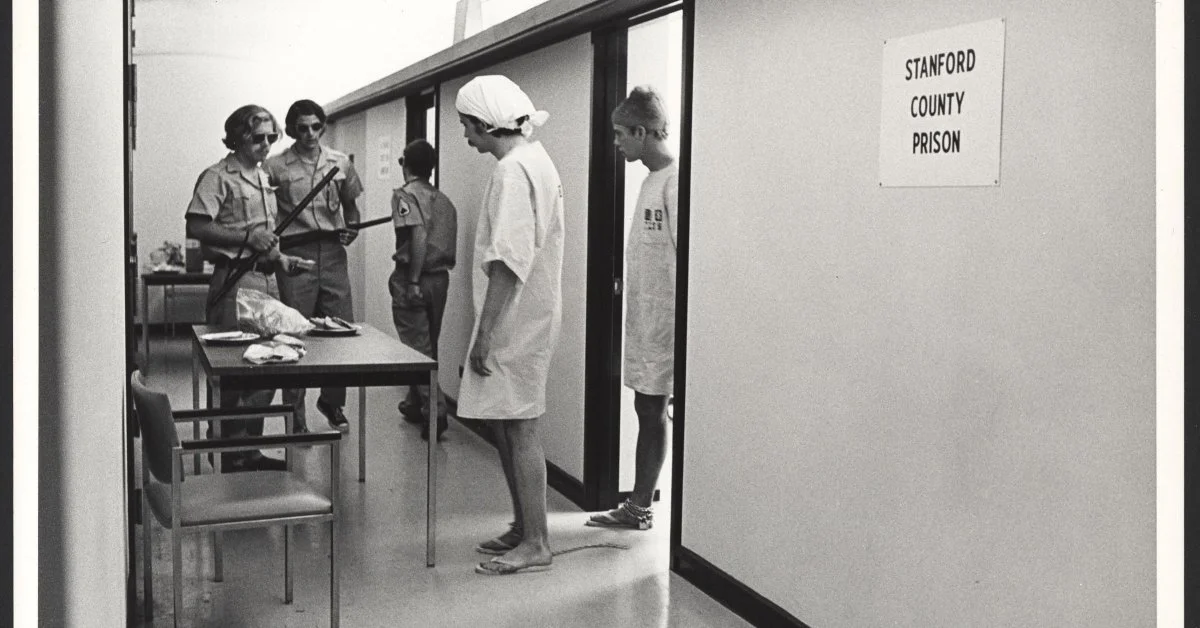

- time.com What the Stanford Prison Experiment Really Means

A new docuseries challenges half a century's worth of received wisdom about the influential social psychology study

- www.theguardian.com The inspiring scientists who saved the world’s first seed bank

The long read: During the siege of Leningrad, botanists in charge of an irreplaceable seed collection had to protect it from fire, rodents – and hunger

- www.scientificamerican.com Earth Could Be Alien to Humans by 2500

Unless greenhouse gas emissions drop significantly, warming by 2500 will make the Amazon barren, Iowa tropical and India too hot to live in

- thespinoff.co.nz On being undeniably, irretrievably old

David Hill is in his ninth decade. In a touching tribute to his late friend, he challenges some myths about 'old farts'.

David Hill is in his ninth decade. In a touching tribute to his late friend, he challenges some myths about ‘old farts’.

- www.theguardian.com How oligarchs took on the UK fraud squad – and won

The long read: It began as a routine investigation into a multinational called ENRC. It became a decade-long saga that has rocked the UK’s financial crime agency. Now new documents illuminate a case that has rewritten UK law and is set to end with a huge bill handed to taxpayers

This seems like it would be a dry read, it's not.

-

Is the US an Ochlocracy?

anacyclosis.org What Is Anacyclosis? - Anacyclosis InstituteWhat is Anacyclosis? The theory of anacyclosis (ἀνακύκλωσις in Greek) represents the culmination of ancient Greek political thought...

- www.businessinsider.com Corporations raised $16 million to oppose Oregon's universal basic income plan. They won.

Voters opposed an Oregon ballot measure that would have given $1,600 annually to all state residents.

- www.wired.com They Searched Through Hundreds of Bands to Solve an Online Mystery

After 17 years, a group of Redditors have identified “The Most Mysterious Song on the Internet.” It’s just the beginning.

For years, a small but heavily engaged community has gathered online, entirely dedicated to the goal of identifying a single elusive song. On Monday, following an exhaustive search, they announced they’d found it.

Now that "The Most Mysterious Song on the Internet” has been located, it leaves behind an entire subculture of “lostwave” music that stretches from cassette tapes to Spotify. Even amid their success, many investigators are unsure about what happens to the community now that its goal has been achieved. What happens to lost media once it’s been found?

We now know the song in question is called “Subways of Your Mind” by FEX, but until Monday, it had lived up to its sobriquet for 17 years. The song was recorded off the German radio station NDR in the early ’80s and was just a question mark on a cassette case until 2007, when it was digitized and posted to various Usenet newsgroups and music forums along with requests for the internet’s help in identifying the track. No one knew what it was.

A 2019 article in Rolling Stone tracks how the song’s ambiguity and retro charm helped draw in a community of music lovers and amateur researchers. The community would grow and shift along with the internet itself, moving from YouTube to Reddit to Discord, eventually coming back to Paul Baskerville, the DJ who would have played the song in the first place. He couldn’t find it in his collection of over 10,000 vinyl records, and talking to Rolling Stone, he admitted, “I don’t know what all the fuss is about [...] I don’t think it’s a particular [sic] interesting song.”

This is a relatively common reaction to lostwave, the general term for these unidentified pre-internet songs, which didn’t really have a niche before the search for “The Most Mysterious Song” carved one out. But for music lovers who are used to Genius and Shazam, an unidentified song is both a splinter in the mind and an opportunity to delve into a hidden, undigitized culture.

“Lostwave searches promote community collaboration and participation beyond the scope of digital platforms,” says Josh Chapdelaine, a professor of media studies at Queens College. “They provide people a chance to contribute to investigations that anyone with a critical approach can advance.”

The first advancement in years came in May, when a user on the buzzing Reddit community r/TheMysteriousSong found a reference to Hörfest, a contest for amateur bands the radio station held every year in Hamburg, Germany. “It was a very likely way to solve our riddle,” says Arne, a moderator of the subreddit who posts under the handle LordElend (Arne declined to give their last name, citing privacy concerns), “since this was a good explanation as to why an amateur band tape would have been aired on NDR, which usually had high standards.”

A search of local government archives turned up thousands of pages on Hörfest, but they wouldn’t be easy to comb through. “We realized that 800 bands, most obscure and not on Google, will need a larger group of researchers,” says Arne.

Soon, hundreds of people across multiple platforms were collaborating on extensive spreadsheets, listing band members, sounds, songs, and anything else they could find. One of these investigators, who posts using the handle marijn1412, found that a member of a band on the spreadsheets, Phret, had joined a different band called FEX. Getting in touch with the former members of FEX, they confirmed the song’s origin. They waited to announce the find publicly until the band was able to sign off and provide a clearer recording of the song.

“Subways of Your Mind” isn’t the only lost media mystery to be solved recently. In September, an image from a fabric pattern was traced back to its source. Back in June, another lostwave song known as “Everyone Knows That” was found after it had become a viral sound on TikTok. It may have been helped by a song from a popular YouTube video identified in November 2023.

These searches tend to be a lot less specific and focused than the Hörfest data, but no less organized or collaborative, since whether or not they can find the song, people are finding kindred spirits. “Lost media searches have shared community values,” says Chapdelaine, adding they’re “amplified by the dynamic of social media platforms. Platforms incentivize engagement. Lost media searches promote interactivity and participation.”

Which is why the story isn’t over, even if the so-called “final boss of lostwave” has fallen. Since other communities devoted to searches have since found what they were looking for, they’ve been folded into the larger lostwave and lost-media community. As Baskerville saw, it isn’t really about the song, it’s about the search, the sense of participating in a project that adds to cultural heritage—and, maybe, finding some songs so exclusive they haven’t been heard in decades.